The Life and Artistry of Ethel Murray Arntz

March 17, 1881 to June 12, 1961

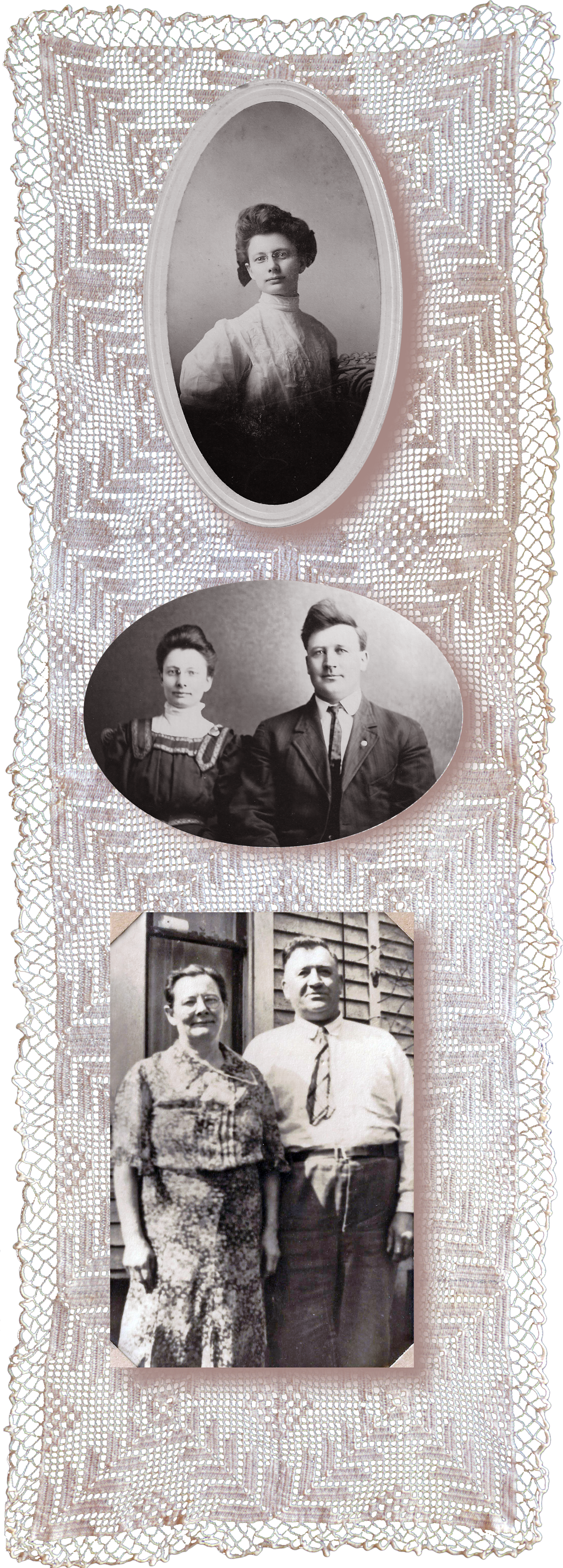

St. Patrick's Day always reminds me of my maternal grandmother, Ethel Murray — could there be a more Irish name? — who was born on March 17, 1881. In many respects, she was the person who raised me, since both my parents worked full-time while raising six rambunctious daughters.

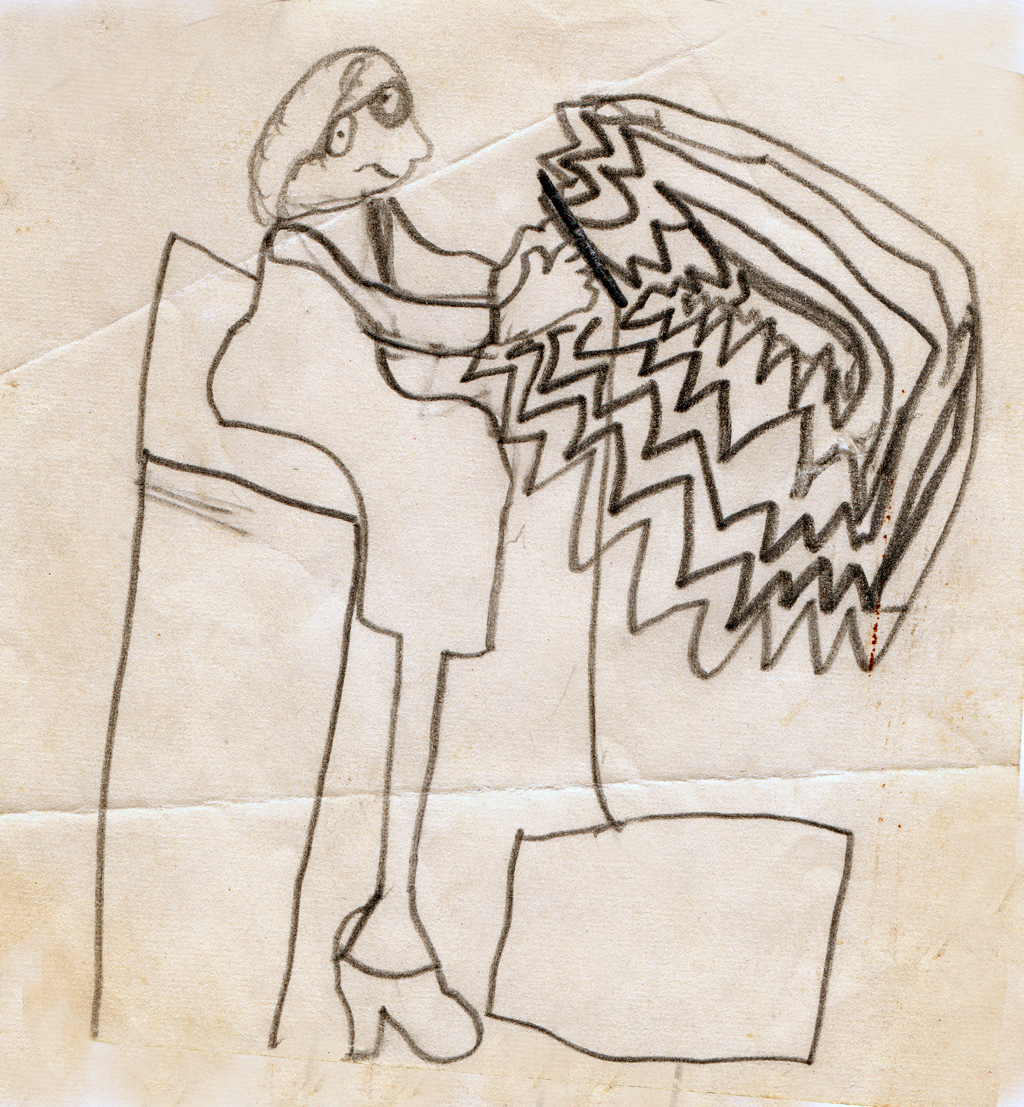

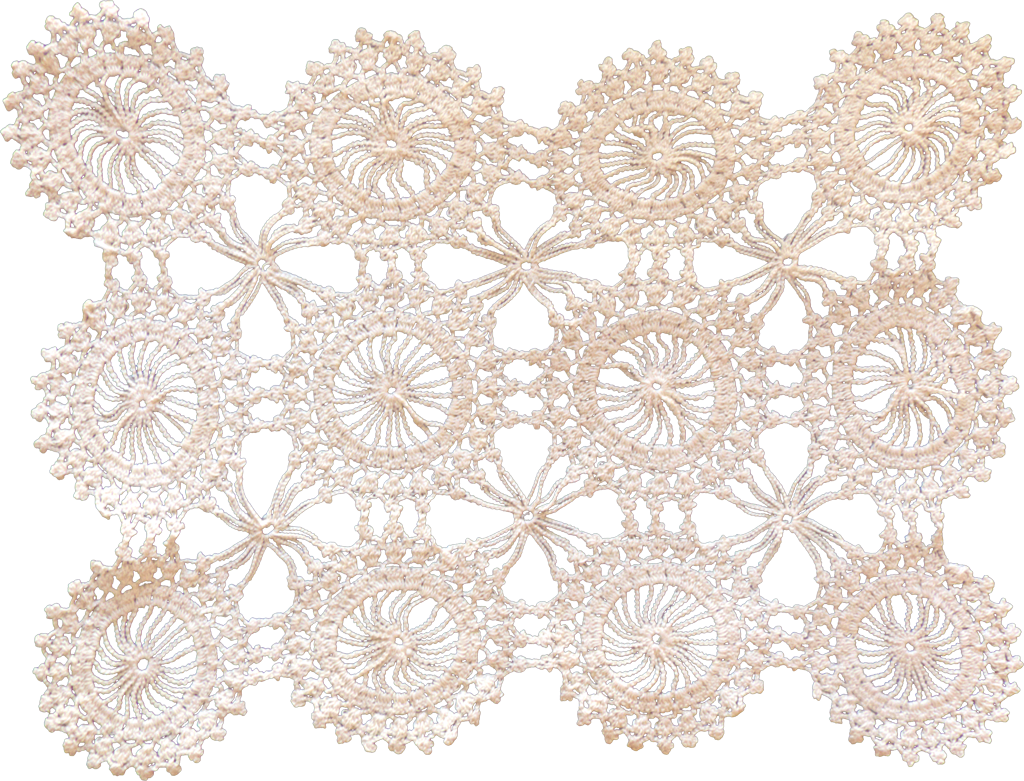

In her later years, her physical activity was severely limited by asthma, so while serving as surrogate parent in a busy household, she produced fabulous handiwork from crocheted doilies to knit afghans. And that's how I remember her, smiling coyly and knitting an afghan in her favorite zig-zag pattern, like in this drawing I did of her when I was six or seven years old.

My sister Ruth made me a wonderful gift of some of the few remaining samples of her work. All of the photos on this page are of work produced at least 55 years ago, since Grandma Ethel passed away in 1961.

This story of Grandma Ethel's life is from my sister, Ruth McDonald Litke:

Ethel Helen Murray was born in Excelsior Township, Sauk County, on 17 March 1881, to Robert Henry Murray and Ella Louise Blood Murray. She taught school as a young woman in Sauk County. She was the family record keeper, and has passed on wonderful stories about her childhood and her adult life on the Dakota plains, where she filed her own homestead claim in Red Lake Township, in her maiden name. The story of Ed and Ethel Arntz begins shortly after their marriage on July 3, 1907.

The homestead farm was located in gently rolling hills northwest of the Village of Burnstad, North Dakota. Three of Ed and Ethel's six children were born on the homestead farm.

Times got hard in western Dakota, where repeated droughts burned up the land and killed off the livestock. During the summer of 1934, Ed Arntz and family pulled out of Burnstad with only their baling rigs, some of their crew, and what few household possessions they had.

This time the family headed east to Grandin, North Dakota, to try for a better life in the Red River Valley. Here along the border with Minnesota, the rich, loamy soil held moisture better. With them traveled their four children — Bob, Don, Margaret and Cliff — two infant sons remained behind in the cemetery at Burnstad. That summer they baled straw and lived in tents, where Ethel cooked meals for the baling crew in the fall.

In 1935, Ed moved the family to a rented farm southwest of Hawley, Minnesota. His brother Rudy and wife Tessie visited that summer and told him about high-paying jobs available in Michigan. Rudy was working in a foundry and earned enough to buy a five-room house and purchase a savings bond every week.

Once again, they pulled up stakes without having much to show for all their labor. Ed and Ethel set off for Michigan in an old(1928-29 vintage) four-speed International truck, and arrived in Michigan a day or so later than daughter Margaret and her new husband, Floyd McDonald. Ed landed a job at Superior Steel & Malleable in Benton Harbor, while Rudy Arntz and his sons worked in a drop forge plant in Jackson.

Ed was diabetic and went blind in one eye in 1940. At that time people did not understand much about the effects of diabetes. They assumed that his blindness was caused by the intense heat at the drop forge plant. He lost sight in his remaining eye about five years later.

Ethel worked during World War II at the Kayo plant in Benton Harbor, making gas mask patterns with scissors. Like many women, she lost her job at the end of the War. Then her asthma worsened, so in the fall of 1950, Ed and Ethel returned to North Dakota to make their home with our family. We girls will always remember fondly taking Grandpa for walks. Irrepressible optimist that he was, each day he thought he could see "just a little more light."

Ed died a few months later at the hospital in Fargo after suffering a seizure. Ethel continued to make her home with her daughter Margaret and family when they moved to Fargo, and later Floyd Lake, near Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. The passing years brought ever-increasing bouts of asthma and pneumonia, and she finally succumbed in 1961.

I recall how Grandpa loved to eat raw hamburger and onions mixed with raw eggs on crackers, washed down by several beers. I have five younger sisters, and he would frequently offer to "settle the little ones down" for our afternoon nap. I would peer over his huge belly to see if anyone was watching; he always fell asleep before we did. My mother says he was such a wonderful dancer — all the Arntz men were so light on their feet. Grandpa loved to fish. When mom was in labor with my younger sister, Jan, he came bursting into the bedroom proudly displaying a stringer of fish he had caught.

This story about my grandparents is my gift to my cousins and their children. In a world crying out for a sense of connectedness, my message is: You belong — genetically and emotionally — to strong-willed, hard-working, honest, laughing, dancing people; people who have experienced pain, frustration, exhaustion, confusion and defeat, and still found the courage to go on. You have good genes!