Floyd McDonald

1911 - 1997

When I delivered my father's eulogy in 1997, I described him as "a small man who lived a very large life". He was married to the same woman for 61 years and raised six children. He lived, worked and traveled all over the United States. There were no limits to his enthusiasm and and imagination, and there's no hall big enough to hold all the people whose lives he touched.

Floyd Elmer McDonald was born in Gardner, North Dakota, on August 10, 1911, the firstborn son of William John McDonald and Emma Brase, and the grandson of Cass County pioneer Alex McDonald, who moved to Gardner from Goderich, Ontario, with his brother William in 1879.

Floyd married Margaret Arntz of Burnstad, North Dakota, on April 10, 1936. The country was still in the grip of the Great Depression, and the young couple moved with Margaret's parents to Michigan, hoping to find jobs in the shops of Benton Harbor. Their first child, Ruth, was born in Benton Harbor in 1937. Janet was born in 1940, while the family was living in a converted fruit shed with dirt floors.

Frances followed in 1942, and remained with the family despite Ruth's efforts to trade her to a neighbor for a puppy! By then Floyd and Margaret both had full-time jobs at a Venetian blind factory, and they bought their first real house in 1942.

World War II broke out in 1941, which meant lots of work for Floyd in the machine shops around Benton Harbor — as much as 10-12 hours a day, six or seven days a week. The stress took its toll, and Floyd suffered a series of nervous breakdowns, which cleaned out their savings. It was during this difficult period that their only son, Kenneth, died a few weeks after birth in 1943.

Evelyn was born in 1945, and the family moved into a larger house. But Floyd fell ill again, and his doctor advised him to get away from the shops.

The family moved back to North Dakota in 1948 when daughter Susan was just two years old. They were soon joined by Margaret's parents, Ed and Ethel Arntz. Initially settling in Grandin, the McDonalds tried raising chickens until they used up most of the money from the sale of their house in Benton Harbor.

In the winter of 1948-49, Floyd's brother Howard mortgaged his farm equipment so Floyd and Margaret could buy a quarter section near Gardner.

"I think that is the only I place I ever lived where I felt the oneness of the earth," Margaret would write.

It was hard work. They grew grain on the rich bottom land, and the older girls herded sheep in the ditches, including the famous ram "Bucky Boodles," who butted Floyd in the behind every chance he got. Bucky was last seen riding away in a taxi with his new owner, who coaxed him into the car with a Milky Way bar.

Winters were harsh, and during the worst storms, blowing snow would block the windows, so they couldn't tell if it was day or night. The spring thaw turned the thick black "gumbo" to super glue, stopping cars and even chickens in their tracks.

They also had a heavy debt load, and not enough income from farming to support a family of eight. In 1950, they sold the land in Gardner to spend a disastrous year on a dairy farm in Lastrup, Minnesota.

They returned to North Dakota in the fall of 1951, where Floyd farmed rented land and Margaret worked in a biscuit factory. During what she described as "the worst week of her life," the entire family came down with the flu, the furnace broke down and filled the house with soot, Jan froze her legs walking home from school, and Frankie was rushed to the hospital in Fargo with appendicitis. In 1952, they bought 160 acres of land without buildings near Argusville. The entire family became the live-in maintenance crew at a Catholic High School in Fargo, where I was born in 1953. Ruth married Ray Litke in May, 1955, and moved to Texas.

Floyd farmed the land between bus routes. The crop was hailed out the first year and flooded out the second. So they put the land in the soil bank, and Floyd followed the harvest with custom combining crews, while Margaret worked at the Grand Recreation Parlor in Fargo.

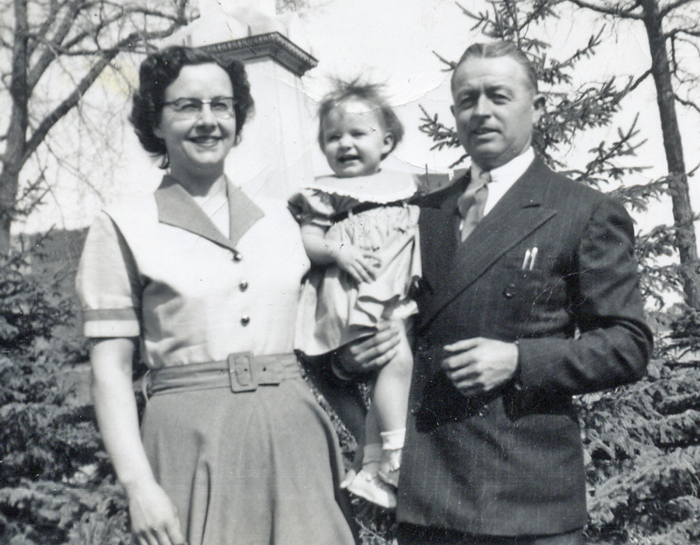

April, 1955

It was a great relief when they were able to move into their own home in Fargo in 1956. Floyd worked for a construction company while Margaret clerked at various stores. A powerful tornado tore the roof off the house in June of 1957. I was struck by a car and sustained a concussion while crossing the street in the spring of 1959, the day of Evy and Sue's Confirmation.

Sue, Dad, Mom and me, April, 1960

In August, 1960, they bought "Sunlite Grocery," a small grocery store on Little Floyd Lake north of Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. They worked long hours, since the store was open 15 hours a day, seven days a week.

Ruth and her daughter Kateri with Floyd and his parents, at the lake in 1960

Fewer hands were available as the years went by. Jan married Jim O'Keeffe in October, 1960, and Frankie married Don Trigg for the first time (they would remarry on the same date 20 years later) in June, 1963.

Margaret and Floyd began wintering in Florida in 1964. Evy, Sue and I accompanied them on the first trip south, and the two older girls remained in Florida. Evy married Hunt Paulling in June, 1966 in Leesburg, Florida. Sue moved to Titusville and was married for the first time in December, 1969.

My high school graduation, 1972

The last little little chick flew the coop in 1972, when I went off to college in Bemidji, then graduate school in Burlington, Vermont. Floyd and Margaret built a new home in Frazee, Minnesota, but spent more and more of their time exploring the country with a small camper or travel trailer.

40th anniversary, Frazee, Minnesota, 1976

Celebrating Floyd McDonald

The entire family gathered in Florida in August, 1991, to celebrate my father's 80th birthday. All of the daughters, and even some of the grandchildren, wrote tributes. The following is excerpted from my contribution:

I don't know too many people who grew up on a lake named after their father. But when we moved to Sunlite Grocery, there was no doubt in my mind that the sign identifying the nearest body of water as "Little Floyd Lake" was put their in honor of Floyd McDonald.

How did such a funny little guy survive the birth, childhood and adolescence of six hard-headed, high-spirited daughters, most of whom were a head taller than he was?

My father' s only real defense was his remarkable sense of humor. Floyd McDonald was a terrible tease! It was his way of showing affection, but it was also a pretty effective means of protecting his big gang of girls. With his merciless teasing, he helped us weed out the boyfriends who weren't worth keeping. I myself dated "Evinrude," "Square Head," and "Right Guard," to name a few. The ones who couldn't take it didn't stick around very long.

I always figured I was Daddy's pet, although I would eventually learn that there was more than one claimant to that title! Not that it mattered much. There were so many of us, I'm not sure he really knew one from another. For a long time, I thought my name was "Ru-Ja-Fra-Ev-Su-Marion."

But not being able to tell us apart didn't prevent him from being terribly proud of all of us. Until his dying day, he routinely stalked cars with license plates from Minnesota, Kansas, Colorado, North Carolina and Québec for the purpose of pinning down the drivers and inflicting upon them his life story and photos of his children and grandchildren.

All my best childhood memories are bound up with memories of my father. I can see him now working in his garage, that big, cool, dark and mysterious place full of well-kept, purposeful-looking tools. And treasures recovered from our neighbors' trash cans (one of our joint projects was a weekly neighborhood dump run).

Was there anything he couldn't fix? I don't remember any of our cars ever going to the shop, and the yard was always full of rehabilitated cars, trucks, trailers and snowploughs. All of our coolers, freezers, fans and cash registers were second-hand scrap that he salvaged, cleaned, repaired and returned to service. I know at one time we had fourteen used refrigerators — mostly full of cold beer for the summer tourists.

The years at the store — the closest thing Mom and Dad ever had to a comfortable existence — were made possible by mother's wits and by father's ability to fix things. Floyd McDonald's self-sufficiency extended to such thankless tasks as the too-frequent cleaning of the Sunlite Grocery septic tank (our house was about 20 feet from the lake). Will any of us ever forget the time he said, "Whew! I gotta take a breather!" as he sat down on a chair inside the septic tank?

I was fortunate enough to grow up on, and more often than not, in, a lake. When I was still very young, Daddy taught me how to run a two-horse outboard motor. First I drove while he fished, but eventually he let me go out on my own, and I took long, slow rides around Little Floyd Lake. When I was older, I graduated to an Arkansas Traveller with a 35-horse Johnson. It was the fastest thing on the lake. We loved to creep up next to some fancy speedboat, gun the motor and leave them sloshing in our wake. He used to take me water skiing with that rig, and when we "hit it," the nose of the boat reared up like a bucking bronco!

When I was 12, a major change took place in my life. Not puberty, which arrived about the same time, but the acquisition of a Honda 90 trail bike. Daddy supposedly bought it for hunting, but I don't think he ever got to warm the seat. At first, he let me drive it as long as I "stayed in the yard." When I had put 50 miles on the odometer and worn deep ruts all around our property, he turned me loose. Willie Minix, the local cop, kindly looked the other way, even though he knew I was under age. I rode that bike for 20 years until it finally died of natural causes in faraway Vermont.

Earlier I said that Mom and Dad's success at Sunlite Grocery was due to their mechanical and mathematical ability, but really the most important ingredient was simply that they were very nice people, who honestly liked their customers and enjoyed talking with them and trying to be helpful. Mom and Dad taught us to speak to everyone who walked through the door at Sunlite Grocery, and this easy contact with strangers has been a big help to me in every job l've ever held.

I remember how surprised I was when I moved to the East and discovered that in that part of the world, polite conduct does not mean always speaking to the people behind and in front of you in a checkout line. And not all motorists give the high sign to all oncoming cars, whether they know the driver or not, like my father always did.

He drove with two feet, as do I. Never mind the driver's ed guys who dock you points for it. From his early teens, he drove every possible vehicle from tractors to big trucks and everything in between. So far as I know, he never had an accident. In 1965, we started spending the winters in Florida, and I loved those long drives! We were always up and on the road by 3:30 a.m. The four of us — Mom, Dad, me and "Smelly Shelley", our Pekinese — shared a thermos of coffee and the front seat of a pickup truck as we watched the sun come up over America.

My parents loved animals, and maybe that's why my father's deer hunting expeditions were doomed to failure. Daddy always "got his deer," though. He was made of burlap-covered cardboard boxes mounted on four big metal dock poles. We ran a mop through him and hung an old stuffed pair of antlers from one end of the mop. We pinned gumdrops on his face to give him eyes, a nose and an ear-to-ear grin. The name changed from year to year — "Dad's Deer," "Father's Fawn," etc. — but the same motley critter was always waiting for him on the front porch of the store, when he came home from hunting, invariably empty-handed. And every year, Daddy got big tears in his eyes when he saw it.

Maybe what I liked best about my growing up years were my father's stories: of custom combining in the "dirty thirties," Harold's roller skating rink and the time his date picked Daddy up and set him down on the bar, tunneling a fort complete with electric lighting into a 75-foot- high snowbank behind the barn, hitching rides on the train from Gardner to Grandin. My father's stories are as much a part of my youth as if I had lived these experiences myself.

Floydie, thank you for those stories, for your boundless enthusiasm, for your friendliness, ingenuity and warm-heartedness. Thanks for laughing so much, and thanks for crying every time you said goodbye to me. Thanks for letting me grow up a terrible tomboy, and for giving me the freedom to make my own mistakes.

Your daughter,

Ru-Ja-Fr-Ev-Su-Marion

Visiting in Florida, 1990

With his beloved Consuela, 1995

When the annual migration to Florida became too difficult, they bought a mobile home and retired to Green Cove Springs, Florida, in 1976. There they remained until the fall of 1996, when declining health brought them back to the Midwest, to be closer to daughters Jan and me in Kansas City.

Their 61st wedding anniversary found them apart for the first time, living in separate nursing homes. Floyd McDonald passed away on May 25, 1997.